The History of Chess Variants

Since Chess, as it is currently played, is not the original game, the history of Chess variants starts with the history of Chess. As H. J. R. Murray puts it after calling the majority of Asian people chess players in A History of Chess, It is in the wider sense, in which I have just used the word, that I propose to use chess in this book. I include under it all the games which I traced back to the Indian chaturanga, and all the freak modifications that have been attempted from time to time

(pp. 28-29).

From Chaturanga to Chess

The name of Chess most strictly refers to a game that took its present shape in Europe and has its rules codified by the World Chess Federation (known by its French acronym of FIDE). This game can be traced back to an Indian game called Chaturanga, whose name meant the four arms of the military.

It comes from chatur, meaning four, and from anga, meaning arms, used in reference to the military, just as the English word army

is. In fact, this was a common term for the Indian army at that time, because it had four main parts, these being the infantry, the horses, the elephants, and the chariots. Notably, these are all represented in the game, which underscores its invention as a board game simulation of warfare.

This game was played on an 8x8 uncheckered board called the ashṭāpada. Although there is no historical documentation of the game from its earliest days, the most trustworthy accounts describe it as being very similar to Chess, differing mainly by having weaker pieces and a few differences in rules. Some have claimed that Chaturanga was originally a four-player game, Chaturanga for four players, but this seems less likely, because the four player game has not had the influence or spread of the two player game, and the inclusion of the number four in the name Chaturanga is not a reference to the number of players. But since the Indians did not keep any extensive writings on the game, we may never know for sure what the original form of Chaturanga was.

The Persians picked up the two player game from contact with India, calling it Chatrang, which was a Persian corruption of the Sanskrit name. According to Henry Davidson, Persians began the practice of informing the opponent when his King was attacked by saying the Persian word for king, shaw. Later, to avoid disputes over whether someone had said shaw, they made it illegal to move the King to an attacked space. This changed the object of the game from capture of the King to checkmate. While our words check, checkmate, and chess do derive from the Persian shaw, Davison's claim that the Persians introduced check and checkmate into the game lacks adequate documentation, and other Chess historians claim that checkmate was the rule in the Indian game.

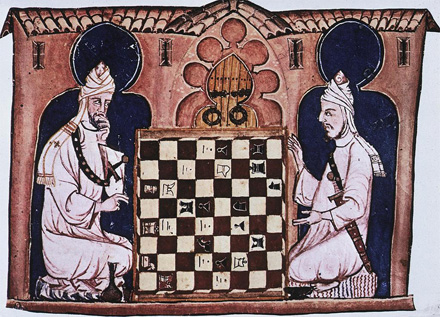

Muslims picked up Chatrang during their conquest of Persia (633-654 CE), calling it Shatranj, which was an Arabic approximation of the Persian name. Unlike the Indians and the Persians, the Muslims took up an active interest in the game, and they started to produce lots of literature on it. It is mainly thanks to Muslim writings that we have knowledge of early Chess. Although we are lacking original documentation on Chaturanga, we are not lacking any on the rules of Shatranj, which is the earliest form of Chess we have detailed accounts of. While Muslims did play some Chess variants, such as the large Tamerlane Chess and the circular Byzantine Chess, they did not, as best we can tell, make any changes to the rules of Shatranj itself. The main Muslim influence on Chess was on piece design. Because artistic representations of people and animals were forbidden in Islam, they adopted the practice of representing the pieces more abstractly. This influence can be seen in today's Staunton pieces, which are mostly abstract.

As with most other games, some Muslims considered Chess forbidden (haram), but this ruling was disputed by other Muslims. First of all, the Muslims did not discover Shatranj until after the death of Muhammed (632 CE). So, there was no mention of it in the Qu'ran or the Hadiths. While Islam does forbid gambling, games of chance, and idle amusements, some Muslims supported the playing of Shatranj by pointing out that it is a game of perfect information, not one of chance, and it is a simulation of war, not an idle amusement. Since people do enjoy playing games, and Shatranj was one of the few games allowed in the Muslim world, this may explain why it became more popular with the Muslims than it had been with the Indians or Persians before them. Besides that, the Muslims were unified by religion, not by geography, and they tried to spread their religion by military conquest. As they succeeded in this, they would also spread knowledge of Shatranj to other lands, and as these other lands became Muslim, Shatranj would gain the same favoritism in these lands that it already received under Islam.

Thanks to the Umayyad conquest of Hispania (711-788 CE), Islam spread to the Iberian peninsula, where Spain and Portugal are currently situated. This is the likely time when knowledge of Shatranj made it to Europe. For several centuries, Europeans played the game by essentially the same rules as the Muslims. There were sometimes tweaks to the rules, and there were some large variants that didn't gain the same popularity as the 8x8 game. In the 12x8 German variant Courier Chess, the Courier piece moved just like the modern Bishop. In Grant Acedrix, described in a medieval codex made for Alfonso X (1221 - 1284) of Castile, the Cockatrice piece also moved as the modern Bishop. Each game also had some new pieces that didn't make it into modern Chess. During the Renaissance, a new form of Chess emerged in which the Bishop and the Queen gained the same long-distance moves they have now.

Emergence of a New Chess

In the late 15th century, Chess started moving in the direction of becoming modern Chess. Thanks to different researchers working with different information, there has been some controvery over where and how this started. I hope to pool together what different researchers have known by reviewing what they have said on the subject in a more or less chronological order. Doing this will help us place each one's claims within the context of what was already known and what has later become known. With many documents now available online, this has become easier than it has in the past. I can now look up many past works on the subject, do text searches to find what I'm looking for, and get computer translations of foreign language texts.

19th Century Authors on a Spanish Origin

In The History of Chess (1860), Duncan Forbes said, Our modern game appears to have originated in Spain, at least the earliest records of it that we possess are found in the works of Vicent and Lucena, about a.d. 1495.

(p. 132). Francesc Vicent had Libre dels jochs partits dels schacs en nombre de 100 printed. Unfortunately, no copy is extant. Luis Ramírez de Lucena is a Spaniard who published Repeticion de Amores e Arte de Axedres eon CL iuegos de partido. It contains 150 (CL) chess problems, 75 being by the old rules, and 75 being by the new rules. Forbes admitted that he had seen neither book, but Lucena's book is now available. The link goes to the Library of Congress, which will let you download a PDF of the original publication. There is a German translation called Berliner Schach-Erinnerungen nebst den Spielen des Greco und Lucena, which even if you can't read either language has the advantage of diagrams with modern Chess piece images. Unfortunately, I have not found an English translation. Without going into much detail himself, Forbes says An interesting account of the works of these writers is given in the

(p. 132).Chess Player’s Chronicle,

for 1852

The work he mentioned has an article called Classical Writers Upon Chess

, presumably by Howard Staunton, the editor of the publication, as it is not credited to anyone else. It references U. Ewell's translation of Vogt's Letters on Chess, but since it refers to them in the third person, it cannot be by them. It tells us The honour of being the first practical writer upon Chess is generally given to Vicent, of Valencia, in Spain. His work was printed at Valencia, a.d. 1495

(p. 371).

In Letters on Chess (1848), Vogt tells us that Lucena was studying at the University of Salamanca, and his book is supposed to have been printed about the year 1495

(p. 3). He also shares the full title and concluding text of Vicent's work, and this tells us it was printed in Valencia on May 15th, 1495. He says,

The title runs thus in the Catalan language : —

“Libre dels jochs partitis del scachs en nombre de 100, per Francesch Vicent. En Valencia, Lope de Roca, 1495." It concludes with the following :—

“A loor e gloria de nostre Bedemtor Jesu Christ, fonc acabat lo dit libre que ha nom libre dels Jochs partitis dels scachs en la insigne ciutat de Valencia e estampat per mans de Lope de Roca, Alemany, e Pere trinchet librere a XV dias de May, del any MCCCCLXXXXV.” (p. 8)

In 1897, the German author T. von der Lasa said, Ich setze den Beginn des allmähligen Überganges zum neuen Spiele in die zweite Hälfte des 15. Jrh., etwa um 1475, und folge übrigens der allgemeinen Annahme, die Änderung sei von Spanien ausgegangen.

(Zur Geschichte und Literatur des Schachpiels, p. 169). Bing translates this as I place the beginning of the gradual transition to the new game in the second half of the fifteenth century, about 1475, and by the way follow the general assumption that the change originated in Spain

. With reference to Vicent's book, he identifies it as being from 1495, but says wir wissen aber nur den Titel und die Schlussworte, sind also im Unklaren darüber, ob sich der Inhalt auf das alte oder schon auf das neue Spiel bezog

(p. 172) Bing translates this to but we only know the title and the concluding words; thus, we are unclear whether the content referred to the old game or to the new one.

He made efforts to find Vicent's book but was unable to. Unlike Forbes, von der Lasa is able to read Lucena's book. Regarding the date of this book, he says Die Zeit für das Werk des Lucena, das keine Jahreszahl trägt, lässt sich dadurch bestimmen, dass der Schachtheil desselben dem bereits als Thronfolger und Johann III. anerkannten Kronprinzen von Spanien, dem Sohn Ferdinand's und der Isabella, dessen delphinicas manos der Autor kusst, gewidmet war. Dieser Prinz starb aber am 4. October 1497

(pp. 173 - 174) With a space added to Schachtheil, Bing translates this to The time for the work of Lucena, which bears no date, can be determined by the fact that the Chess section of it was dedicated to the crown prince of Spain, who was already recognized as heir to the throne and John III., the son of Ferdinand and Isabella, whose delphinicas manos the author kisses. However, this prince died on October 4, 1497.

The grammar is a bit garbled, but since other authors have gone over this, I know what he means is that Lucena dedicated the book to Prince Juan of Spain, but Juan died in 1497, which means Lucena's book was not written any later than 1497.

So far, the idea of a Spanish origin is based on the earliest known works on the new Chess being printed in Spain. Vicent's book was printed in Valencia in 1495, and Lucena's was probably printed in Salamanca around 1497. Von der Lasa's date of 1475 is probably an estimate made by assuming it took about 20 years after its creation for books on the game to be printed, as he does not mention any documents earlier than Vicent's book on which this date could be based.

20th Century Authors on an Italian Origin

During the 20th century, the common belief expressed by Chess historians was that the new form of the game began in Italy. The main argument for this came from H. J. R. Murray in the early part of the century. Writing later in the century, Davidson and Golombek continued this idea.

H. J. R. Murray

In A History of Chess (1913), H. J. R. Murray challenged this opinion, arguing that it probably began in Italy no earlier than 1485 (Murray, pp. 777-778). At the time Murray was writing, he tells us The earliest records of the new game occur in three MSS., two of French and one of Catalan origin, and in the printed Spanish work of Lucena. There are other early Italian MSS. which contain problems of the new game, of which one has been assigned to the end of the 15th c. It is difficult to decide between the claims of Italy, France, and Spain to have been the earliest home of the new chess; but Italy has probably the best claim.

(p. 778). By manuscripts, he means they were hand-written. The work of Lucena was printed on a printing press. The French manuscript he discusses is Le jeu des esches de la dame Moralise. He doesn't seem to mention the other one. The manuscript of Catalan origin is Scachs d'amor from Valencia, Spain. Murray dated this to the late 15th century but did not know what year it was written. He tells us that the first Italian work on the new game ... was Damiano’s Qvesto libro e da imparare giocare a scachi et de li partiti, which was printed in Rome in 1512

(p. 787). The Library of Congress will let you download a PDF or view it online as Libro da imparare giochare a scachi, et de belissimi partiti, reuisti & recoretti, & ... da molti famosissimi giocatori emendati, in lingua spagnola & taliana nouamente stampato. Since this is from the 16th century, I'm not sure what Italian manuscript he thinks is from the late 15th century. It's also worth mentioning that Damiano is from Portugal, not from Italy. So, the language may be Italian, but it's not the work of an Italian.

Immediately upon what I just quoted, Murray launches into his argument for an Italian origin, saying The French morality in using the name eschés de la dame enragée points, I think, to an Italian rather than to a Spanish parentage. Lucena makes no claim in his work for a Spanish discovery, and expressly states that he had collected the material for his book in Rome, all Italy, and France. Egenolff is too late for his evidence to be allowed much weight, but his name welsches Schachspiel (Italian chess) shows that the game spread to Germany from Italy

(p. 778). However, Murray's reasoning is unsound.

La dame enragée

The reference to la dame enragée comes from Le Jeu des Eschés de la Dame, moralisé (p. 21). Note that the title does not use the term. In this work, which Murray says is from the 15th century, the author says in French, Touttefoys l’inuention est à moy estrange à cause que il s’appelle de la dame enragée. Et croy que c’est le tiltre que aucuns ont bailié qui estoient hommes indiscretz

. Based on some translations I got, this might be translated as However, the intention is strange to me because it is called the enraged lady. And I believe that this title has been given by some men who were indiscreet.

Without translating it, Murray draws attention to the author being puzzled by the name, and he claims this throws light upon the origin of the Italian alla rabiosa

(Murray, p. 780). Additionally, a hand-written introduction to the text by a 20th century author (judging by his later citation of Murray) says The name, de la dame enragee, is, of course, a translation from the Italian, explaining the rabiosa as an epithet for the new and powerful Queen

(p. 11).

Searching Murray's book for rabiosa, I find a couple sources. One is a 16th century copy of Bonus Socius with 54 problems of the reformed chess ‘a la rabiosa’

(Murray, p. 620). The other is a manuscript copied in Rome by Joannes Chachi on the date Ex anno 1511 die Mercurij 30 Julij

, which would be Wednesday, July 30th, 1511 (Murray, p. 727). Since both of these are from the 16th century, neither could be the source for a French manuscript from the 15th century. We might imagine that the Italian term is older than our records of it, or that the French manuscript is more recent than Murray claims.

If it's the former, it may just be from misogyny, as Marilyn Yalom surmises. She says, Whenever women become overtly powerful, there is almost always a backlash. This was true even for the chess queen. In France and Italy, backlash expressed itself in the label

(Birth of the Chess Queen, p. 204). She then gives a vile example of it from 1534, Les controverses des sexes masculin et féminin by Gratien du Pont, who wrote a different insult for women on each square of the chess board. Douglas Galbi, who, fair warning, is sympathetic to du Pont, describes this work in more detail in his article Rise of the all-powerful chess queen & Gratien Dupont’s protest.mad queen’s chess

If it's the latter, there may be a more specifically historical explanation for the term rabiosa. In the year 1511, the queen of Castile, Joanna of Castile (1479 - 1555), was already said to be mad. Rumors of her madness began during her rocky marriage to Philip the Handsome. Thanks to the untimely deaths of older siblings and a young nephew, she succeeded her mother to the throne of Castile in 1504. But her husband took the power to rule away from her on the grounds that she was unfit to rule. When her husband died in 1506, her father Ferdinand came to rule Castile, and when he died in 1516, her son Charles ruled in her name. In favor of her having mental problems, her parents were second cousins, one of her grandmothers allegedly had mental problems, her mother allegedly disciplined her like someone running the Spanish Inquisition, multiple family members died while she was young, and she had a bad marriage. But it's also possible that Philip, Ferdinand, and Charles were politically ambitious and savvy men who were willing to treat her as a political pawn for their own ambitions, and she did not have the will or ability to oppose them. Whether or not she was actually mad, she came to be known as Joanna the Mad or in Spanish Juana la loca. With this in mind, perhaps someone with an objection to calling the piece a lady chose to call it a mad woman as an indiscreet reference to the Castilian queen. If so, this would point to a Spanish origin for the game rather than an Italian one.

Whether or not rabiosa was coined with a particular mad queen in mind, it would have been a derogatory or unflattering term, and it would probably not have been used by the game's creators. It's more likely that the piece was originally known by a term meaning lady, as Spain, France, and Italy all have a name for the game meaning chess of the lady. These are axedrez de la dama in Spanish, eschés de la dame in French, and scacchi de la donna in Italian. So even if the Italian rabiosa predates the French dame enragée, this does not show that the new game was invented in Italy.

Lucena

If Lucena had actually mentioned where the game came from, I expect Murray would not be focusing on what he didn't say. Although Lucena collected material in his travels to Italy and France, this does not imply that he first learned of the new version of Chess in one of these countries. In Chess: A History (1976), Harry Golombek says of Lucena's work, William Lewis, in his Letters on Chess by C. F. Vogt, claimed in 1834 that much of it was copied from an earlier work in Catalan by Vicent

(p. 98). Golombek goes on to name the work by Vicent already mentioned above. Lewis is the translator, and Vogt is the author. Upon looking this up, the text reads, It is very probable that Lucena copied many of his from Vicent's work, the rarest of all the printed books on Chess, and probably the first Chess book that ever was printed. I have not been so fortunate as to meet with a copy, nor do I know any one who has

(pp. 7-8). So, Golombek misrepresented what was said. This was an estimate of probablity, not a declaration of known fact, and it was made without any knowledge of the content of Vicent's book. This makes it a lot less authoritative.

In an article called Classical Writers Upon Chess

from Howard Staunton's Chess Player's Chronicle, the author, presumably Staunton himself, objects to Vogt's claim. It says,

We are not disposed to agree with this opinion, for the following reasons :—Lucena's work was published without any date or place being named, but by the universal voice of tradition has been assigned to no year later than 1495, the very year in which Vicent's treatise was printed. The dedication to Lucena's work states it to be written by Lucena, son of the very learned Doctor and Reverend Prothonotory, Don Johan Remirez de Lucena, studying in the university of Salamanca. From such a dedication in that age we may infer that it was printed at Salamanca ; Vicent's treatise appeared at Valencia. Now, although the crowns of Arragon and Castile were united in 1469 under Ferdinand and Isabella, so great was the jealousy that subsisted between the two kingdoms for many years, that it is very improbable that a student of the University of Salamanca, a town of Leon, one of the most distant provinces of the kingdom of Castile, should have been acquainted with and based his work on a treatise published on the 15th of May, in the same year, by an inhabitant of Valencia, a city in one of the most remote provinces of ihe Arragonese monarchy. The composition of a book upon Chess with numerous woodcuts would be much too difficult a task, and printing too scarce at that time, to admit of so speedy a reappearance. (pp. 371-2)

His main argument presumes that both works were published the same year, though all he has to back this up is the universal voice of tradition.

When Vogt gave the year of 1495 for its publication, he was so not dogmatic about it. T. von der Lasa dated it to 1497 on the basis of its dedication to Prince Juan, who died in 1497. More recently, Ricardo Calvo has shown that it couldn't have been printed any earlier than 1496 and that it was probably printed in 1497. In his article Love, Chess and Literature in Lucena, Calvo identifies the printers of Lucena's book as Leonardus Hutz and Lope de Sanz de Navarra. Hutz was printing books in Valencia until 1496, then set up shop in Salamanca, and then moved to Zaragoza after 1497. Besides mentioning that Prince Juan died in 1497, Calvo also tells us that the prince got married in 1497 and recieved the city of Salamanca as his dowry. Additionally, Juan's marriage was a political marriage to Margaret of Austria, and it was also arranged for his sister Juana to marry Margaret's brother Philip, both children of Maximilian I, who would later become Holy Roman Emperor. One of the active ambassadors for bringing this about was Lucena's father. These details provide the occasion for Lucena's dedication to the crown prince, which places the printing of the book in 1497. Since Hutz came from Valencia to Salamanca, this could also account for how Lucena might come across a copy of Vicent's book so far away from Valencia.

Furthermore, Murray mentioned that Lucena did research for his book in France and Italy. Going to or from Italy, he may well have passed through Valencia, which was a port city on the Mediterranean. Since Lucena's father was an ambassador for King Ferdinand, this would suggest that Lucena came from somewhere in Aragon. Salamanca was simply where he was attending university.

As to whether Vicent influenced Lucena, neither side is really convincing. Murray mentions Vicent only in a couple footnotes, as Vicent's work is lost. Instead of arguing that Vicent didn't influence Lucena, he just doesn't bring it up. He also neglects to raise the possibility of a connection between Scachs d'amor and Lucena even though he does mention that work, and it is also from Spain. In neglecting the possibility that Lucena learned about the game from earlier Catalan works, he is conveniently ignoring what doesn't fit with his narrative that the new game began in Italy.

Welsches Schachspiel

The phrase welsches Schachspiel is German for Welsh Chess game. The German for Italian Chess is Italienisches Schach. However, welsches Scachspiel may be a misquotation. Murray includes an extract from Egenolff in an appendix, and its first line reads Ein ander art das Schachspil zu ziehen/so mann nennet Current oder das welsch Schachspiel

(p. 810). Note that it says welsch Schachspiel, and Bing translates this line to Another way to draw the chess game is called Current or the German chess game.

In contrast, Google translates it to Another way of playing chess is called current or French chess.

Looking up the German word welsch, it can mean Welsh, but it can also mean foreign

or pertaining to the Romance languages and their speakers in general.

It is in this last sense that the word could describe something from Italy, as Italian is one of the Romance languages, but we should bear in mind that French and Spanish are also Romance languages, and the word could also describe something from France or Spain. So even if understood in that sense, it does not imply an Italian origin.

Henry Davidson

In A Short History of Chess (1949), Henry Davidson says,

And it is to Italy that we are indebted for the modern game of chess (that is, the game in which bishops and queens have their extended moves). It is true that the first text detailing the modern game was written in Spain by Lucena in about 1490. But Lucena himself asserts that his material came from Italy. Modern chess was played in Italy before 1500, in Spain during the earliest decades of the sixteenth century, in France and England by about the middle of that century, and in Germany by 1600. (p. 130)

Conveniently, Davidson does not actually quote Lucena. It would seem that Davidson has misread Murray, who wrote that Lucena had collected the material for his book in Rome, all Italy, and France.

There is certainly a difference between knowing how to play the game and collecting positions from games people have actually played. Since his book is mainly a book of Chess problems, Lucena probably means that he got the game positions from games he observed or played in France and Italy. He may have already learned how to play in Spain. I don't know where this 1490 date comes from. No other researcher has given this as a date for Lucena's work. Even Murray says it was circa 1497. So it appears that Davidson was either bad at research or bad at proofreading.

Harry Golombek

In Chess: A History (1976), Harry Golombek says, Since it was in Italy that the Renaissance flowered, it was natural that it should have been Italian chessplayers, stimulated by the revivification of the arts and the sciences, who were chiefly responsible for the change in the game

(p. 81). This is not a good argument. It is just a romantic idea that the Italian Renaissance must have been the impetus for the new version of the game. I suppose it is just harder to feel romantic about the Spanish Inquisition, which was happening around the same time, but our favorite things don't always have to come from the best circumstances. When he does argue for an Italian origin a little more substantially, he mainly just repeats Murray's three points in the same order, saying,

It is clear that the revitalized game arose in Italy, since players came from abroad to Rome to learn of the developments. Lucena, for instance, states in his book that he went there to gather material for writing about the new form and its rules. Moreover, the French term, which came later than the Italian, is obviously a translation of rabiosa. In 1536, Christian Egenolff published a fresh edition in Frankfurt-am-Main of the book by Mennel called Schachzabel. This gave the rules of the old game, and Egenolff added a description of the modern one under the heading, Ein ander art das Schachspil zu ziehen/so mann nennet Current oder sad Welsh Schachspiel. This means,Another way of playing chess which is known as the Current or Italian game.It seems, oddly enough, thatwelschhere is equivalent to Italian. (p. 83)

I quoted it in full to point out some differences from Murray. First, Golombek confidently states that the new game came from Italy, whereas Murray hedged his bets more, saying It is difficult to decide between the claims of Italy, France, and Spain to have been the earliest home of the new chess; but Italy has probably the best claim.

Second, Golombek neglects to mention that Lucena also gathered material in France. Third, he asserts that the French term la dame enragée came after the Italian term rabiosa, yet according to Murray's dating of the documents these terms are found in, the French manuscript is earlier than the Italian documents. Regarding the Egenolff text, Golombek clarifies that Egenolff is the publisher and Mennel is the author. He also correctly uses the term welsch instead of welsches, and he notes that it's odd that it would mean Italian, though he still goes along with Murray in saying it does.

New Evidence for a Spanish Origin

New evidence for a Spanish origin centers around new information about Vicent, Lucena, and the Scachs d'amor document. Since none of the researchers I cited had even seen Vicent's work, it would be of interest to get some information on its contents, particularly on whether it was actually about the new form of Chess, which its title alone cannot tell us. Regarding Lucena, it would help to have evidence that he learned about the new form of Chess in Spain. And what do we know about Scachs d'amor? Murray didn't factor it in because he didn't have a precise date for it. Can we get a more precise date and show that it is even earlier than Vicent and Lucena? In 1998, Ricardo Calvo presented a paper called Valencia Spain: The Cradle of European Chess, which addresses all of these questions. In what follows, I will examine what Calvo and some other researchers have to say on this, and I will also bring up some other evidence in favor of a Spanish origin.

Vicent

In note 18, Calvo brought up an author named Cardanus who printed a Chess book. He says, in his treatise

This is just to provide context for saying that De rerum varietate

(1557), Cardanus remarks that he composed his chess book with

great effort, and makes several comments about the best way of printing diagrams. The practical

problem was to print a black piece on a black square, and Cardan suggests a sensible way of

solving it: instead of making the square completely black, it is better to make the square striped

.Cardan mentions as a bad example that

Calvo claimed this was a reference to Vicent's book, saying those who printed the Spanish book confounded everything

.The question is, which Spanish book is Cardan referring to? Lucena's book contains no mention of his printers, and only

typographical research has established recently that the printers were Leonard Hutz and Lope

Sanz. But on the contrary, Vicent's book stated clearly in the colophon that the book had been

printed by Lope de Roca "Alemany" and Pere Trincher. So, Cardan was obviously referring to

Vicent's book, and this book was therefore well known in Italy in the middle of the XVI century.

I will first point out that it is possible to refer to the people who made something without having their names on hand. The PDF of Lucena's book illustrates the problem Cardanus was addressing, as its own black spaces were black, and black pieces on black spaces simply had a white outline around them. But maybe the idea Calvo had in mind here is that having the printers named implies that Vicent's book was more popular, and because of this, it had to be the one Cardanus was referring to. This seems to be a slim basis for arguing that Vicent's book was more popular, and I could counterargue that Lucena's was more popular on the grounds that we still have copies of it, and all copies of Vicent's book are lost. Besides that, being more popular is not any guarantee of which book was being referred to. Lucena's book was clearly around back then, as surviving copies of it prove, and I see no reason to think he couldn't have been referring to Lucena's book. One more thing is that Vicent's book was a Catalan book printed in Valencia when it was under the crown of Aragon. It was not in Spanish, and the country of Spain did not yet exist when it was printed. So, of the two books, Lucena's is the only one it would be accurate to call Spanish. For these reasons, I do not consider this a solid lead on Vicent's book.

Regarding a Chess player and author named Salvio, Calvo says in Note 19,

In his very rare book "Il giuoco degli scacchi", Naples 1723, (which had its first partial edition in 1604), Salvio describes a chess match between Michele di Mauro and Tommaso Capputi. The astute Capputi prepared for the match by reading the chess book written by his opponent. On the contrary, Michele di Mauro used for his training other chess books: "...prende il Bove, il Rui Lopes e il Carrera, L'Alemanni, il Gironi e gli altri erranti..." These books are known: " il Bove" (The Ox) is Paolo Boi's book. Ruy López, Carrera and the Spaniard Girón also had chess books in use. But no one knows "L'Alemanni". Chicco deduced that Salvio, who frequently misread names, was referring to Vicent's book, confounding the name of the printer Lope de Roca "Alemany" with the name of the author. So, the book of Vicent was still known and used in Sicily in the 17th century.

Since the other books were about the new form of Chess, and Michele di Mauro was preparing to play a game of it, we may assume that L'Alemanni was also about the new Chess. As mentioned in the text quoted from Vicent's book by Vogt, one of its printers is identified as Lope de Roca, Alemany

. This wouldn't be the only time someone referred to a book by its printer rather than its author. When Murray mentioned Egenolff, he was naming the printer rather than the author of the work he was referring to. So, it's reasonable to suppose that Salvio was referring to Vicent's book, and that the context in which he was referring to it indicates that it was about the new form of Chess in which the Queen and Bishop, as we call them in English, had their modern moves.

In Valencia lectures part 2: The amazing story of the lost chess book, Arnie Chipmunk tells about José Antonio Garzon Roger's book The return of Francesch Vicent. In this book, Roger claims to have reconstructed Vicent's book by comparing Chess problems in Lucena's book, the Cesena and Perugia manuscripts, and Damiano's book. Roger argues that the Cesena and Perugia manuscripts are the work of Vicent during his Italian period. In chapter 3 of his book, Roger lists several early documents on modern Chess. He lists the Perugia document as #15 and the Cesena document as #16.

He says of the Perugia document, We have no doubts about its author being Francesch Vicent.

It has 72 Chess problems, 46 of which are according to the new rules. He notes that one of the problems is the same as Lucena's 150th problem and Damiano's 72nd, and that the book includes Spanish terms. One more detail indicating the Valencian origin of its author is a diagram for the initial position of draughts

, or checkers as I would call it in America, as this game appears in Valencia around the same time as modern Chess.

The Cesena document was discovered in 1995 by Franco Patesi, who has described it in an Italian article called Il manoscritto scacchistico di Cesena. His article lists numerous problems from this text in an algebraic text format that English speakers can still read, and it identifies other documents the problems also appear in. These include Civis Bononiae, Lucena, Damiano, and the Göttingen manuscript. In sharing some details from his article, I will quote translations made by Bing. Regarding its language, he says The text is written mainly in Italian, but sometimes Latin is used, mainly for older problems. In addition, several Spanish expressions appear, inserted into the text. More rarely, expressions appear in other Romance languages.

Additionally, he says, One might also be tempted to reduce the Spanish component to a few elements, but in particular the systematic use of some frequently used technical terms, such as

Commenting on its handwriting, Patesi tells us tomar

for to take or lance

for stroke, suggests the actual intervention of a Spaniard in the compilation.this is not the work of a copyist who has transcribed the content in a professional manner; If this compiler was a professional, he might rather be a chess master.

Based on it having both old and new Chess problems and that the handwriting and other details indicate it to be from the 16th century, he suggests a date of 1520. As to its author, he notes that no author is named but says My personal impression is that it was a Spaniard who copied from Latin and Italian sources, at least from a Latin manuscript of the Civis Bononiae and from a more recent Italian manuscript of the Perugian codex family.

Patesi also has an English article on Cesena called The last encyclopaedic manuscript.

Roger says the Cesena document has all the material of the Perugia document but with a different presentation, and he says it is the work of the same author, obviously a Spaniard.

This document has 357 problems, 156 of which are for modern Chess. Besides being linked to the Perugia document, it appears linked to Damiano's book too. Roger says, It also probably contains the draft that was used to make Damiano's book, since Damiano's 16 subtleties and 72 problems are presented, selected and marked by the author.

Based on this, he concludes that Damiano was a pseudonym for Vicent.

So he has identified three texts he believes are by Vicent, and he finds in them all the problems of modern Chess from Lucena's book (listed as #12) except for one. He says the original idea behind Lucena's book was basically a literal translation of Vicent's treatise excluding the mates in 2.

Unlike Vicent's book, though, Lucena's also added several problems for the old form of Chess. He lists Vicent's book as #11. He says it contained 79 problems of modern Chess, and that it is fully contained in the Cesena manuscript. Of course, this is based on his reconstruction of it through comparing these documents, as an actual copy of the original still hasn't been found. While he has no doubts about his theory, I have not gone over all the same evidence he has, and I can imagine other possibilties, such as someone copying from Lucena and others. So, while it's an intriguing theory, I am not as fully confident in it as he is.

Lucena

Calvo identifies the printers of Lucena's book as Lope Sanz and Leonard Hutz. Before they worked together in Salamanca, Hutz had been working in Valencia. In note 10, he says of Hutz and his former partner Petrus Hagenbach that the two of them appear printing together in 1491 in Valencia

and then lists off several books they printed together up through one dated April 13, 1496. This places Hutz in Valencia when Vicent's book was printed there. This also indicates that Lucena didn't publish his work until at least 1496. So, Vicent's book predates Lucena's. Additionally, Calvo says of Hutz and Vicent's printer Lope de Roca, Several documents prove also a friendly personal relationship among them.

Given this, it is likely that Hutz brought copies of Vicent's book with him to Salamanca, and he could have sold one to Lucena before he started on his book. In that event, it's possible that Lucena learned of the game from Vicent's book. The main objection to this is that Lucena did research for his book in France and Italy, and this must have taken him some time, especially given how slow transportation was back then. But if Columbus could make it to America and back in less than a year, I suppose Lucena could have traveled to Italy and France and back within a year or less.

Lucena might have acquired Vicent's book earlier if he had himself been in Valencia rather than Salamanca. Calvo says, The Lucenas belonged to the Aragonese crown (14). Juan de Lucena, the father of the chess player Lucena, was ambassador of King Ferdinand, and when the Inquisition prosecuted him, in Zaragoza in 1504, there is a dramatic

letter still preserved wherein Juan de Lucena reminds the monarch of all his past services to the crown.

Zaragoza is on the map as Saragosa in Aragon. In note 14, referenced in the quotation, Calvo says Lucena was assuredly not from Salamanca, because he stated so. Almost certainly he came from someplace in the kingdom of Aragon, probably the area close to Medinaceli and Almazán.

Since these two places were not on the map of Spain shown above, I had to look them up. They are both in Castile, northeast of Madrid, close to the border with Aragon. The closest place I see in Aragon on the map would be Calatayud, whose name is written across both Castile and Aragon. This places him closer to Valencia prior to his attending university in Salamanca. Calvo also says, Lucena the chess player had travelled

I'll add to this that Aragon had a land border with France, and Castile did not. So, whether Lucena and his father went to France or Italy first, they were likely to pass through Aragon or Valencia. As we'll see in the next section, there is also good evidence that the new Chess was known in Valencia prior to Vicent's book, and Lucena could have already known about the game at an earlier date.in Italy and

France

with his father before writing his chess book, and the port of Valencia was the most

sensible departure route when going to Italy.

Scachs d'amor

Briefly known as Scachs d'amor, this Catalan manuscript has the full title of Hobra intitulada Scachs d’Amor, feta per don Franci de Castelvi e Narcis Vinyoles e Mossen Fenollar, sots nom de tres planetas, ço es Març, Venus e Mercuri, per conjunccio e influencia dels quals fon inventada. It was discovered in 1905, and Murray mentions it in A History of Chess, but he doesn't give it a more precise date than the end of the 15th c.

(p. 781).

In his paper, Calvo argues that Scachs d'amor is older than Vicent's or Lucena's works and that Lucena probably knew of this work. As mentioned in the longer title, the authors are don Franci de Castelvi, Narcis Vinyoles, and Mossen Fenollar. The first of them to die was Castelvi, who died on November 6th, 1506, making this the most recent date the work could have been written. But he thinks it was written even earlier. Narcis Vinyoles is named with the title of mossen in a 1488 work, but in this work, he is named without title even though Fenollar is named with that same title, and Castelvi is named with the title of don. This suggests that the work was not written any later than 1488. This is already earlier than Vicent's work from 1495 or Lucena's from 1497. But other factors may suggest an even earlier date. The first work printed on the printing press in Valencia was in 1494, and it contained poems by each of the three authors. Given that Schachs d'amor is a hand-written manuscript, it probably doesn't date from much later than when these three authors started having their works printed.

In Valencia and the origin of modern chess, Arnie Chipmunk goes over many of the same points Calvo raised and adds some new ones made by José Antonio Garzón Roger and Govert Westerveld. According to both of them, he tells us, there are obvious hints within the Scachs d'Amor poem to Isabella's actual coronation.

But he points out only one. Stanza 54 says the Queen is given the sword, the sceptre and the throne.

. Roger points out that that Queen Isabella I was crowned with the sword of justice raised in front of her, and the sceptre and throne were given to her.

Since Isabella had her coronation in December of 1474, this would suggest a date for Scachs d'amor that follows her coronation but is not too much later.

One thing to be said against this is that in Dr. Josep Miquel Sobrer's English translation of Scachs d'Amor, the relevant line from stanza 54 reads Taking the orb, sceptre, and throne

. Notably, it says orb instead of sword. In Birth of the Chess Queen, Marilyn Yalom noted how unusual it was that Isabella used a sword in her coronation. She says At the very head of the procession rode a horseman carrying a naked sword with the point downward, resembling a cross. Isabella chose to revive this ancient symbol of militant faith and justice, although the traditional monarch’s symbol in Castile was a scepter

(p. 188). A little further on, she says of Ferdinand, He was shocked at the use of the unsheathed sword, which he considered a symbol of

(p. 189). So, if orb is the correct translation, this might not be an allusion to her coronation. The Catalan word in question is pom, and when translated to English, the Catalan dictionary just linked to gives male privilege

usurped by the queenpommel of a sword

as one definition and Golden ball (also called world or globe) carried by kings in their hands as an emblem of supreme power

as another. It could mean either. In favor of it being a synecdoche for sword, the word is directly related to the English pommel, it is not related to any English word meaning orb, and the Catalan dictionary gives other words an orb is known by. In favor of it meaning orb, the orb, sceptre, and throne are all traditional symbols of royal power, and in Caxton's Game and playe of the chesse, printed in England in 1474, the illustration of the King shows him with all three with the orb called an apple of gold

(p. 19). Notably, Caxton's book was translated from French, and the French for apple is pomme. But even if orb is the correct meaning, it does at least seem to be an allusion to Isabella gaining the crown of Castile.

But Roger may have provided an even more decisive way to pinpoint the date Scachs d'amor was written. Chipmunk says, Garzon Roger also discovered that in June 1475, Mars, Venus and Mecury were in close conjunction at the Valencian sky.

This is significant, because the tail end of the full title says in English under the names of three planets: Mars, Venus, and Mercury, by conjunction and influence of which the work was devised.

To verify that the conjunction happened, I went to https://astronomes.com/sky-map/ and generated a map of the sky from June 30th, 1475 in Valencia, which shows the three planets nearby each other around the constellation of Taurus. I decreased the magnitude to remove most stars from the image, but one star remains that resembles Mercury. To tell them apart, I found out that the precise hex color of each is different. Mercury's color is #D3D3D3, and the star's color is #FFFFFF. A question does remain, though, concerning how common conjunctions of these three planets were. Checking the same day of the year for 1470-1500, I do not see these planets in the same constellation except for 1475.

We don't know for sure that the authors of Scachs d'amor created the new Chess, and we can't rule out that someone in another country didn't invent it even earlier. All we can really say is that we have no evidence of this. However, Juan Reyes La Rosa has put forth a theory that he believes would demonstrate that the authors of Scachs d'amor are the creators of the new Chess. In The Astronomical Origin of Chess (2024), he argues that the authors were fitting pieces along a Fibonacci sequence in support of the idea that the distances of the planets from the sun also fit into a Fibonacci sequence. This was supposed to be a coded way of expressing heliocentric beliefs at a time when geocentrism prevailed. In a Fibonacci sequence, the first number appears twice, and each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two. Starting with 1, a Fibonacci sequence can look like this: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and so on. He measures the mobility of each piece by adding up the legal moves it may have from each space it may reach, but he has to include the Ferz, which he calls a primal queen,

and he has to make adjustments to the Pawn and Ferz to fit the pieces into a Fibonacci sequence. Without making these adjustments, we get White Pawn: 140, Black Pawn: 140, Ferz: 196, Knight: 336, Bishop: 560, Rook: 896, and Queen: 1456. (I confirmed these values by having a GAME Code program generate them.) It's true that 336=140+196, 896=336+560 and 1456=560+896, but 196 is not 140+140, and 560 is not 196+336.

For his idea to bear out, he tries to give the Pawn a value of 112 and the Ferz a value of 224. So he has to decrease Pawn moves by 28 and increase Ferz moves by the same number. For the Ferz, he adds 26 moves by appealing to a Knight's move from the first rank, which he applies to every space on the first rank, and he adds 2 more by appealing to an ability to leap two spaces diagonally, which he applies only to the space the piece begins on. But this is inconsistent. He should apply both rules to the same spaces, but for every space in the first rank, this would add 12+26=38 extra moves, and for just the space it starts from, it would add only 2+4=6 extra moves, neither of which would give the desired result. For the Pawn he removes the 14 capture moves to the last rank and the 14 en passant captures. However, the 14 en passant captures were never part of the original calculation of 140. It simply added up each possible normal capture of a piece on a space and each possible move to an empty space. Also, if you were to take into consideration the effect of en passant by not counting double moves, this would reduce the moves by 8 instead of 14.

Besides the mathematical problems, Schach d'amor never mentions the rules he is appealing to. It does not mention anything about Pawns being unable to capture on the last rank, and it does not describe the rule of en passant capture or illustrate it with a move. Considering that he is using bad math with rules and a piece that are not part of the game, things are not adding up, and it looks like the pieces do not fall into a Fibonacci sequence. As the compound of the Rook and Bishop, whose moves do not overlap, it was inevitable that the Queen's total number of possible moves would equal those of the Rook and Bishop combined. It's more interesting that the Rook's total number of moves equals the total number of the Knight and Bishop combined, and the Knight's are equal to the total number of the Pawn and Ferz combined. It's enough to make me wonder whether some mathematical considerations like these were behind the game, but adding Bishops and giving Pawns double moves, which allowed for these mathematical equivalencies, also improved gameplay, and as the diagonal counterpart of the Rook, the Bishop was an obvious piece to add. So, he has not effectively demonstrated that the game described in Schachs d'amor was created for abstruse mathematical and astronomical reasons, and without this, he fails to demonstrate that its authors invented the game. While they may well have, his case that they did is a dead end.

However, I will point out something that makes it more likely that they did invent the new game. In England in 1474, Caxton's Game and playe of the chesse was printed. This was an English translation Caxton had made of an older French book, and it covered only the old version of Chess. Given that this is the book on Chess that was being printed in England at this time, it serves as evidence that the new form of the game was not yet known in England. This might be because the new game had not yet been invented, or because knowledge of it had not yet made its way to England. Whichever is true, this suggests that the new Chess was not invented much earlier than Scachs d'amor was written.

One point in favor of Scachs d'amor preceding Lucena's work is that its rules are less like modern Chess than those described in Lucena. Although the game presented in Scachs d'amore is perfectly legal by modern rules, it does not include any en passant capture, any Pawn promotion, or castling. In Letters on Chess (1848), Vogt says of Lucena, It appears that in his day a Pawn might take en passant, as is now the law in most parts of Europe, and that when it reached the last line it assumed at once all the powers of a Queen

(p. 4). We might expect that the game described in Scachs d'amor would have allowed Pawn promotion to a dama, since Pawns had always been allowed to promote to the piece it replaced. But en passant may be new to Lucena.

In Classical Writers Upon Chess

from The Chess Player's Chronicle for 1852, it says that in Lucena, Castling ... resembled our own method, but occupied two moves instead of one, the Rook being brought close up to the King, and the King being placed over him to K. Kt. square, or Q. B. square, on the next move

(p. 372). However, what is described as castling may actually be an application of a different rule. In describing the King's powers of movement given in Lucena's book, Antonius van der Linde says in Quellenstudien zur Geschichte des Schachspiels (1881), Der König (rey) darf im ersten zuge in jedes beliebige dritte feld (d. h. entweder als neuer Fers nach c1, gl und e3: oder als Alfil nach g3 und c3 ; oder als Pferd nach g2, f3, d3 und c2) springen (saltare); er darf aber weder aus dem schach noch an dem schach vorüber springen

(p. 231). This may be translated as, The king (rey) may jump (saltare) on the first move to any third square (i.e. either as a new ferz to c1, g1 and e3; or as an alfil to g3 and c3; or as a knight to g2, f3, d3 and c2); but it must not jump out of check or past check

What this means is that on its first move, a King may leap to any space two spaces away so long as it doesn't pass through check or use this power to escape check. What looks like castling is the King using this power after a Rook has moved next to it. The author actually does mention this rule, but he indicates that this is the rule in Ruy Lopez rather than Lucena. It would appear, though, that Lucena and Lopez were following the same rule. Still, this version of Chess does seem to be transitional between Scachs d'amor and modern Chess.

Further Remarks on a Spanish Origin

A Spanish origin makes better sense of the linguistic evidence described on the Queen page. The word dama, which is both the Catalan and Spanish name for the piece, is used in 15 different languages. In constrast, the word dame is used in only 4, and the word donna is used only in Italian. If Chess truly had an Italian origin, one might expect donna to be the more popular term for the piece. While the greater popularity of dama might possibly be from Spain becoming a world power at the time, this is a stretch, because Spain became a world power mainly in the New World, and the languages using the Spanish term are European. In particular, dama is used in several Romance languages, in several Slavic languages, and in Albanian, which is neither.

So far, I have pieced together evidence, and it supports a Spanish origin. But it may be helpful to have a scenario in mind by which the new game was invented. Queen Isabella was the direct descendant of Alphonso X, and she ruled over the same kingdom, the kingdom of Castile. This makes it very likely that she possessed his codex that described the game Grant Acedrix, in which the Cockatrice moved as a modern Bishop and started next to the King and its companion piece. It's rather likely that she played the game herself or showed the codex to people who would find it interesting. Before gaining the throne of Castile in 1474, she had already married Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469. Although Ferdinand was not yet king, this marriage would have put her in contact with Aragon and other kingdoms under its rule, including Valencia. Given that some of the authors of Scachs d'amor had close ties with Ferdinand, they may have had occassion to meet Isabella and learn about Alphonso X's codex. When Isabella was going to inherit the throne of Castile, this may have inspired someone with knowledge of Grant Acedrix to honor her with a new form of Chess that borrowed the Cockatrice and combined its power with that of the Rook for a stronger Queen.

In time, other changes were made to Chess, such as castling, en passant capture, and Pawn promotion to any non-royal piece in the game. Together, these changes to the game helped speed it up and make it more decisive. This new game grew quickly in popularity, and a few factors may have helped with this. First, it was a better and more exciting game than the earlier Shatranj. Second, the printing press, invented around 1440, allowed for quicker and more widespread communication than had existed during the Middle Ages. Third, during its early days, Ferdinand and Isabella were actively persecuting and driving out Muslims, which may have reduced the popularity of the Muslim form of Chess. As we know it in the west, Chess had generally come together in its present form by the 19th century. But it was only in the 20th century, following the formation of FIDE in 1924, that its rules were officially codified.

The Origin of Chess

Although there is solid evidence linking modern Chess to the Indian Chaturanga, this, by itself, doesn't establish Chaturanga as the original game. Although an Indian origin is the prevailing opinion, some have claimed that the game has another origin. Besides India, some of the main options include Persia, Uzbekistan, and China. Persia is the nation that the Muslims learned of Chess from, and some of our Chess vocabulary still has its roots in Persian. Uzbekistan is the location of the earliest Chess set to ever be recovered. West of China and northwest of India, it was once part of the Soviet Union. China is a major power with its own version of Chess that is clearly related to the western versions.

Sam Sloan on a Chinese Origin

In The Origin of Chess (1985), which is online as a single webpage, Sam Sloan argues for a Chinese origin. He claims that the game or a precursor to it was known in China as far back as the second century BC. He says:

There are two references to chess in ancient Chinese literature. The first was from a collection of poems known asChu Chi. The author was named Chii Yuan. He was the most famous writer in the Chou Dynasty (1046 - 255 BC). He killed himself by jumping into a lake. The second is from a famous book of philosophy known asShuo Yuanwhich cited Chu Chi. It is from the Han Dynasty (206 BC - 221 AD). Both are well known to any student of Chinese literature.

Searching the Chu Ci (as an online version calls it) for 象棋, I found it in a poem identified as 29 招䰟. The line with it says 菎蔽象棋,有六簙些。

, and it translates to There are six kinds of Chess.

Before this, it mentions scholars and women sitting together, and just before the line about Chess, it says Zheng Wei demon plays, come and miscellaneous. [or: Zheng Wei demon play, come to the mischief] The knot of excitement is the first to show alone.

When I did a search for Zheng Wei, it came up as a name of a woman. So it could be the name of one of the aforementioned women playing a game. After the mention of Chess, the next line says Divide and advance together, and force each other better

in the traditional translation or Divide Cao and advance, and force each other to be more forced

in the simplified translation. This line includes the 相 character used for the Minister in Xiangi, whose name also sounds like xiang, though apparently not with that meaning. This line might be about moving game pieces in a board game simulating warfare. The next line translates to Become a lord and make a profit [or: Cheng Cheng and Mu], call five white.

When I translated the first clause by itself, I got just the word Success

. While it is not clear what is going on, it could be about a woman playing and winning a board game. But even if that is what it is about, it does not describe this game in enough detail to tell if it is related to Chess.

The text of the Shuo Yuan is at the same site. Searching it for 象棋, I found a poem identified as 14 善說. The line that has it says 燕則鬥象棋而舞鄭女

and translates to Yan fights chess and dances Zheng Nu, excites Chu to cut the wind [or: excites the cutting wind], practices color with obscene eyes [or: practices lustful eyes], and streams with ears [or: hears loud ears]

. The poem as a whole seems to be about some conflict between Emperor Qin and the king of Chu. While this could be the context in which a Chess game is set, this is not made clear. Also, fighting Chess is only one thing Yan is said to be doing, and the other things don't seem so related to Chess. It is really not clear that this is even describing a board game. So I don't consider these two earlier texts with 象棋 to be solid evidence that the game now known by that name existed back then.

After mentioning these, he says A more recent reference to chess came from the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279 AD).

But evidence of Xiangqi in the Song Dynasty is not evidence of a Chinese origin for Chess. By this time, the Muslims had already brought Shatranj to Europe. Although Sloan has decried the absence of early enough Indian literature on Chess, he has failed to produce early enough Chinese literature on Chess. So, on that score, neither India nor China has the advantage.

Lacking adequate literary evidence of a Chinese origin, Sloan argues against an Indian origin by saying horses, horse-carts, and chariots do not exist naturally in either Europe or India.

Against this, I will point out that the Bhagavad Gita portrays Krishna as Arjuna's chariot driver. Whether or not horses and chariots were common in India, they both played a central role in Hindu mythology. So, Indians would have known what they were. He later stresses the same point about horses by saying Horses, as stated before, do not exist naturally in India. Tame horses can be found, but not wild horses.

To this I will add that tame horses are the ones that people ride and use to draw chariots. This admission that tame horses can be found in India undermines his argument that an Indian would not have created a game with horses serving as steeds and chariots drawn by horses.

Against Chess having its origin in Uzbekistan, he says Uzbekistan is primarily a desert area, like Afghanistan, and its inhabitants were always primarily nomads. It is hard to believe that they invented a game like chess. It seems more likely that they brought it by caravan from some other place.

Maybe so, but this is hardly convincing. He also adds, At the same time, elephants existed in India and probably in China, but not in Persia, Pakistan or Uzbekistan, although the Persians had heard of elephants.

With this, he believes he has ruled out both Persia and Uzbekistan. But let me point out that Wikipedia has an article called Persian war elephants, and the elephants in the game would have been war elephants, not wild elephants. So, Persia is not ruled out.

David Li on a Chinese Origin

In The Genealogy of Chess (1998), David Li argues that Chess was invented by a Chinese general named Han Xin, who lived in the 2nd century BC. While I have not read the book myself, I did read a review by Peter Banaschak called A story well told is not necessarily true - being a critical assessment of David H. Li's The Genealogy of Chess

. Banaschak claims that David Li has practically nothing besides his fertile imagination to back his claim that Han Xin invented chess.

Jim Png has written a more detailed article called Origins of Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) 12: General Han Xin, which examines the evidence behind the claims made about Han Xin inventing Chess. He finds that there is no real evidence of Han Xin inventing Chess. Notably, one of the stories about him inventing the game mentions the Cannon as one of the pieces, yet cannons would not be invented until over a thousand years later. So he certainly didn't invent the present form of Xiangqi, and there is no evidence that he invented any predecessor to it.

Jim Ong Hau Cheng on a Chinese Origin

In Understanding the Elephant: A Xiangqi Primer Part 1: History of Xiangqi (2016), Jim Png Hau Cheng claims that Xiangqi may have been descended from earlier Chinese games. In particular, he suggests that Xiangqi could have evolved from Liu Bo, which led to Ge Wu, which in turn evolved into an early form of Xiangqi. Apart from also being a board game, Liu Bo has no obvious connection to Chess or Xiangqi. While its rules are unknown, it was apparently a race game played with dice, which would make it more like Candyland than Chess. Its board was not a grid of spaces over which pieces can move. Its main similarity to the Chess board was a square in each corner, but these squares were not connected by other squares, and the Chess board has even more in common with the Monopoly board. The only resemblance between Liu Bo and Xiangqi of any note is that Liu Bo had waterways, and Xiangqi has a river. However, the river in Xiangqi is a border, not a waterway, and it most likely came about by splitting an 8x8 board into two halves, pulling them slightly apart, and placing pieces on the intersections as in Go. Also, if Liu Bo was an ancestor of Chess, and this was the critical connection between Liu Bo and Xiangqi, it needs to be explained why no other regional variants from Asia or India have the river. Even Janggi, which is the regional variant most closely related to Xiangqi, has no river. So, it doesn't look like there is any good evidence for a connection between Liu Bo and Chess.

He does not provide much of a description of Ge Wu, but it seems that it was also a race game played with dice. Each player had six (or later five) pieces that moved over channels. Its pieces included "figures in the shape of the dragon and tiger." (Kindle Loc 1014) Notably, neither Xiangqi nor Chess has any dragon or tiger pieces. Judging from the description, the game has no clear connection to Chess.

Somehow, these race games supposedly led to the invention of an 8x8 Xiangqi by Emperor Wu of the Zhou dynasty, which lasted from 560 to 578 CE. This would be less than a century before the Muslims picked up Chatrang from the Persians. Of course, it is likely that the Persians picked up Chaturanga from the Indians at an earlier date. So, the invention of an 8x8 Xiangqi by Emperor Wu may be more or less contemporary with the time that Chaturanga was purportedly invented in India. However, there are no extant records of Emperor Wu's 8x8 Xiangqi. He allegedly wrote about it in the Book of Symbolic Chess, but there are no surviving copies of that book. Moreover, it has been common to give Chess various legendary inventors, and Emperor Wu might be just another legendary inventor, not the game's real inventor. Without any records of the game, it is impossible to ascertain its connection to earlier games or even to establish that it ever existed.

He does mention that an 8x8 chessboard found in Gu Jin is, to date, "the earliest finding of any eight by eight chessboard." (Kindle Loc 1241) I presume this is a place in China, but I can find no information on a place called Gu Jin or on the chessboard that was allegedly found there. So, it's not much to go on. The best evidence he can provide shows that Xiangqi, as we know it today, was around during the Southern Song Dynasty. As he says, "The Xiangqi that we play today took form no later than the Song Dynasty, or the Southern Song Dynasty to be precise." (Kindle loc 2182) However, the dates he gives for the Southern Song Dynasty are from 1127 CE to 1279 CE, which are several centuries after the Muslims picked up Shatranj from the Persians. In the intervening time, there was contact and trade between China and the Muslim world, and knowledge of Shatranj could have made it to China through the Muslims.

The Evolution of Chess

One of the main things there is agreement on is that Shatranj and Xiangqi are related. With some variations, Xiangqi has all the pieces of Shatranj. Their names mostly have the same meanings, they move similarly, and they start out in similar positions. The games have similar goals, and the Xiangqi board may be made by dividing the Shatranj board in two, slightly separating the two halves, drawing some diagonals, and placing the pieces on the intersections. While we cannot say with certainty exactly where Chess was invented, it was probably within the vicinity of India, China, or the Silk Road. Notably, India and China share a border, and whichever place it was invented in, it could have made its way to the other country in short time. Wherever it was invented, I believe the original game was more like Chaturanga and Shatranj than it was like Xiangqi.

From the perspective of game design, Xiangqi is superior to Shatranj, and this suggests that Shatranj is closer to the original game than Xiangqi is. Shatranj is flawed by the existence of several weak pieces, which can slow down the game and make it harder for either side to win. Xiangqi fixed this problem by weakening and confining the royal piece and some defensive pieces while also increasing the attacking power of the royal piece and adding a new piece, the Cannon, whose powers favor attack more than defense. The result of these changes weakened defense and strengthened offense, making the game more decisive.

Besides being corrected in Xiangqi, this problem has been independently corrected in both modern Chess and the Japanese game Shogi. Modern Chess fixed it by making the weakest pieces stronger. Shogi addressed the problem of slow-moving weak pieces by allowing players to drop captured pieces back onto the board. This increased the mobility of pieces without changing their basic powers. Shogi weakened defense by making more pieces than just the Pawns forward moving only, and it added power to offense by providing promotion for several piece types upon reaching the other side. These changes kept the pieces weaker where they would be used for defense and made them stronger where they would be used for offense. Given that each of these games each corrected a flaw in Shatranj yet are otherwise similar to it, it is very likely that each one of them evolved from a game similar to Shatranj, which itself is supposed to be close to the Indian Chaturanga.

Besides this, Xiangqi includes elements that are not common to other oriental Chess variants. It is the only one with a river, and it is the only one with its particular powers of movement for the General (King), Elephant, Cannon, and Pawn. It shares some of its other features only with Korea's Janggi. Among regional Chess variants, these are the only two played on intersections instead of spaces, the only two with blockable Knights and Elephants, the only two with Cannons, the only two to give each player only five Pawns, and the only two played on a 9x10 playing area. Also, both games can be played with the same equipment, but extra Pawns and some modifications to the board would be required to play other regional variants. It makes sense that Korea would learn the game from China even if the game was invented in India, because Korea is a peninsula whose only land border is with China, and it lies on the eastern end of China while India borders China in the west. Given that the influence of Xiangqi is not as evident in other oriental Chess variants, it seems unlikely that the original game was like Xiangqi. And given that Korea's Janggi is not nearly as much like Shatranj as many other Asian variants are, it seems unlikely that the original game, being much more like Shatranj, had its origins in China.

It is noteworthy, though, that Japan attributes its acquisition of Shogi to China. Nevertheless, Shogi's similarities with Xiangqi do not include most of its uncommon features. It is played on spaces, it has no Cannons, it does not confine any pieces to a particular area of the board, and it includes new features that distinguish it both from Xiangqi and other Chess variants. So it is unlikely that Shogi is based on a game like Xiangqi, as Janggi clearly was, and it is much more likely that it was based on a game like Shatranj, which the Japanese then modified into Shogi.

Among known oriental variants, the one that looks like the best candidate is Makruk, the Chess variant of Siam, now known as Thailand. It is mainly like Chaturanga, but each player's Pawns start on the third rank, as they do in Shogi, and the Elephant moves as the Silver General does in Shogi. While Thailand is further away from Japan than China and probably also had less political and cultural influence on Japan, the geographies of these two countries would have made them both more sea-faring than the more land-locked China, and this would have facilitated cultural exchanges between them. Furthermore, Makruk's differences from Chaturanga are improvements. The more advanced line of Pawns speeds up the game, and giving Elephants the Silver General's move lets them cover the whole board instead of only a fraction of it. This suggests that Chaturanga is the earlier game.

Another possible candidate for the link between Chaturanga and Shogi is Sittuyin, the regional Chess variant of Burma, now known as Myanmar. Like Makruk, its Pawns start in a more advanced position, and its Elephant moves as a Silver General. But it also goes off in a different direction than either Shogi or Chaturanga, and the sea route from most parts of Burma to Japan would have been longer than the one from Siam to Japan. Comparing Sittuyin with Makruk, Sittuyin seems to be an improvement over Makruk, as it speeds up the game even more by allowing free placement of the pieces behind the Pawns. So, it's likely that Makruk came first, and Sittuyin is based on it. Given these considerations, it seems fairly likely that knowledge of Chaturanga spread from India to Siam by sea, and both the Burmese and the Japanese learned of the game through contact with the Siamese.

If Japan did in fact learn of Chess through contact with Siam or another neighbor in between, that would account for why Shogi does not resemble Xiangqi to nearly the same degree as Janggi does. But there are some traces of Chinese influence. The Japanese name for Shogi is written in Chinese characters, though this could be more due to Japan borrowing its writing system from China. A more telling detail is that the Chinese characters used to write the name for Shogi are exactly the same as the Chinese characters used to write the name for Janggi. This suggests that these games originated from a common source or that one influenced the other. Looking at these two characters, the first one is the 将 character for general. This reflects that the Chinese changed the name of the King to General. The second character is the 棋 character for board game, which is also used in the Chinese name for Xiangqi. Besides that, every Shogi piece with a counterpart in Xiangqi uses one of the same characters that get used for the piece in Xiangqi. Still, these similarities could just be due to Japan's use of the Chinese writing system and to the fact that the meanings of the piece names tended to remain the same across different languages. Even more significant than these linguistic similarities is that the Pawns in Shogi do not capture diagonally, a characteristic that Shogi shares in common with Xiangqi and Janggi, though not with Makruk, Sittuyin, or Chaturanga.

Assuming Japan did learn of Chess through China, there are three possible explanations for why Janggi is much closer to Xiangqi than Shogi is. One is that knowledge of Chess passed from China to Japan earlier than it did to Korea, so that the Japanese learned of a game more similar to Shatranj, while the Koreans learned of a game more similar to modern Xiangqi. The second is that China had a weaker influence on Japan than on Korea. This makes sense given that Japan is not on the mainland, while Korea is on a peninsula off of China. The Chinese were able to march right into Korea, and during its history, it was often a vassal state to the current Chinese dynasty. This ties into the third possible explanation, which is that Japan, being a sea-faring nation with several trading partners, gained knowledge of multiple regional Chess variants and synthesized elements of them into their own variants.

One last thing to look at is how culture spread between India and China. India appears to have had the greater influence. Buddhism quickly spread from India to China, then to Japan and Korea. But Confucianism and Taoism, which were of Chinese origin, did not gain footholds in India. They did, however, spread east, Taoism influencing Zen Buddhism in Japan and Confucianism becoming dominant in Korea during the Joseon period. Turning to games, Wei Qi was a hugely popular game in China, spreading to Japan, where it became known as Go, and to Korea, where it became known as Baduk. Yet Wei Qi did not spread to India. It is a very different game than Chess, and the only regional Chess variants to show any influence from it are Xiangqi and Janggi, which both place pieces on the intersections. Given this and the other considerations raised here, it seems more probable that the origins of Chess go back to India than that they go back to China.

Reformers

Because of the extensive analysis that has been done on Chess and the knowledge of opening moves that is required to do well in Chess competitively, some Chess players have proposed replacing Chess with a new game that would provide more challenges and require more original thinking. Examples of this include Capablanca's Chess, Fischer Random Chess, and Seirawan Chess.

Fairy Chess

Some Chess variants were not intended for actual play but were created for the sake of creating fairy chess problems. The term fairy chess was proposed in 1914 by Henry Tate. In December 1918, T. R. Dawson took up this term and published his first article on fairy chess in The Chess Amateur. In it, he mentioned that problemists had occasionally been producing unorthodox problems in a haphazard way, as editors allowed them, and this did not give them much incentive to compose many of them. So, within the pages of this magazine and later The Fairy Chess Review, Dawson provided a place for Chess problems that introduced different rules, terrains, or pieces, and these were collectively known as fairy chess problems.

Chess Variants in Science Fiction

Edgar Rice Burroughs, who was writing books about John Carter's adventures on Mars, centered one book, The Chessmen of Mars, on the Martian game of Jetan, which was similar to Chess in many respects. Some of the fans of his book took up an interest in the game he described therein. When Star Trek aired on TV, it showed Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock playing a three-dimensional form of Chess on a board with multiple levels. Although this was just a prop, fans of the series took up an interest in it and developed rules for Star Trek 3D Chess.