Courtyard

Editor's Note: Courtyard was invented by Leonard

Kalich Sr., and is (or was) a game distributed by FunDynamics. Having made

reasonable efforts to contact them, we can only assume they have gone out of

business. However this may not necessarily be true, so if anyone knows of how we

could contact this company or the inventor, please let us know so we can request

permission to continue publishing this description of the rules. Thank you.

John Ayer

writes:

This is another crossover game. It

was invented by Len Kalich (Leonard Kalich, Sr.) of Troy, Michigan. He

meant to combine the ease of learning checkers with the challenge and variety of

chess. The following abstract of the rules is based on material copyrighted

1984, 1986, and 1987.

The board is ten squares on each side, checkered white and dark, except that the

four central squares are replaced by a walled courtyard. Each player has a

dark square at the right-hand end of the nearest row. Play is on dark

squares only. There are two gaps in the courtyard wall, one square wide,

on the left-hand side as each player faces the courtyard. It is each

players goal to move his king into the courtyard through the entrance on his

opponents side of the board, and so to win the game. A king cannot enter

through the gate on his own side, and no other piece can enter the courtyard

under any circumstances.

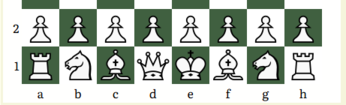

Each player has fifteen playing pieces: a king, four guards, and ten serfs.

Each player starts with his king on the central dark square on his back row,

flanked by his four guards, with the serfs occupying the next two rows.

Capture is by jumping over a piece on an adjacent square to the square

immediately beyond, which must be vacant. Capture is mandatory.

Sequential captures are possible (and mandatory). The only way to avoid

this necessity is to move another of ones own pieces to the square that the

capturing piece would land on (if the player with the move can do this).

If a player fails to make a possible capture, his opponent removes the piece

that could have captured, and then makes his own move. Removing the piece

that could have captured is also mandatory. No piece can ever jump another

piece of its own color.

The king moves one square in any of the four diagonal directions. He can

capture opposing guards and serfs. He cannot capture the opposing king.

The king may capture an enemy piece by a leap that lands him in the courtyard by

the right gate. If a players king is captured, the game continues until

the opposing king enters the courtyard or is captured (making a tie).

The guard moves one or two squares in any of the four diagonal directions.

If a guard moves two squares, they must be in the same direction. He cannot

move one square and then make a leap in the same move. A guard can capture

any opposing piece.

The serf moves one square diagonally forward right or forward left, and can

capture any opposing piece or pieces, but only by leaping diagonally forward.

A serf that reaches the opposite edge of the board remains there inactive unless

its player spends a move returning it to any vacant dark square on his first

row.

Each player makes one move, according to the rules above, per turn. Which

player moves first is determined by lot (alternatively, players or clubs can

agree that white moves first). A player who has pieces on the board but

cannot make a legal move loses, provided the other player can still move.

A player who loses all his pieces loses the game. Conceding a game is done

by picking up the opponents king and setting it down in the courtyard.

The proprietary pieces are quite handsome, and enhance the pleasure of the game.

The dark square are dark red; ox-blood might be about right. Thin golden

lines separate the squares. Golden spearheads on two squares point to the

entrances to the courtyard, which is black, ornamented with a large uncial C in

golden outline, and furnished with removable plastic walls shaped to suggest

plastered stone.

Courtyard was published by FunDynamics in 1983. (Ed.)

photo credits: http://www.abstractstrategy.com/courtyard.html